Cartel? Liner competition increased as trans-Pacific rates spiked

More carriers deploy more capacity as they buy and lease more ships and boxes

It’s seemingly inevitable: As ocean carrier profits soar — and they’re now reaching historic heights — the highly consolidated liner industry will face growing accusations of unfairness and wrongdoing.

The Hill reported Wednesday that Sen. Amy Klobuchar, a Senate Judiciary Committee member, “is working on antitrust legislation related to the shipping industry.” The same day, the watchdog organization Accountable.US accused shipping lines of charging “abusively high fees.”

Social media posts this week alleged that ocean carriers are “profiteering” and “ripping people off.” Over recent months, ocean carriers have been referred to as a “cartel.” In November, Business Insider reported that it received an email from the White House referring to “price gouging by the ocean shipping cartel.”

And yet, the data implies ocean carriers are competing more, not less, with freight prices rising as demand continues to exceed supply chain capacity despite higher carrier competition, not because of artificially lower competition — the definition of a cartel.

Trans-Pacific competition rises

The trans-Pacific is the key trade for U.S. cargo shippers. According to Drewry, Shanghai-Los Angeles spot rates (excluding premium charges) are currently up 152% year on year.

But there are more ships serving the trans-Pacific trade than there were before rates started to surge, and this higher number of ships is being operated by a larger pool of competitors.

According to Gene Seroka, executive director of the Port of Los Angeles, 10 new entrants in the trade served his terminals during the latest peak season.

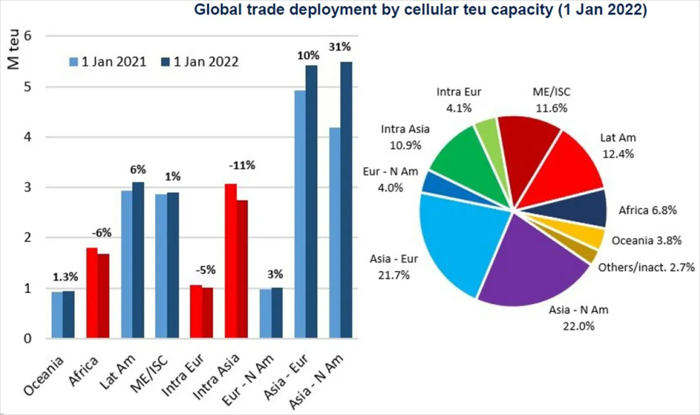

Alphaliner reported a “massive shift” in carrier deployments in 2021, with 22% of global capacity placed in the Asia-North America lane, making it the largest trade in the world after it stole capacity from other routes. Carriers hiked Asia-North America capacity by 1.3 million twenty-foot equivalent units year over year, “a staggering 31.2% increase.”

Alphaliner said that carriers shifted “as much capacity as possible to the trans-Pacific” to chase “irresistible” rates that were higher per nautical mile (including premiums) than in any other mainline trade.

Alphaliner pointed out that the capacity added to the trans-Pacific far exceeded last year’s increase in cargo volume. Traditionally, that would lead to price competition, yet in this case, excess ship capacity has been soaked up by port congestion.

“The capacity increase was needed to compensate for the huge efficiency loss as many ships faced long waiting times at anchorages,” maintained Alphaliner.

A new report this week from Sea-Intelligence highlighted how the recent era of spiking trans-Pacific spot rates coincides with a sharp decrease in market share of the three carrier alliances (2M, Ocean Alliance, THE Alliance).

In 2012-2020, the trans-Pacific balance was 15%-20% non-alliance and 80%-85% alliance. According to Sea-Intelligence CEO Alan Murphy, “Over the past 18 months, there has been a very substantial increase in the share of capacity offered outside the alliances. We are now at the point where 35% of the capacity offered is on non-alliance services.” The non-alliance share has doubled. Chart: American Shipper based on data source: Sea-Intelligence.com, Sunday Spotlight, issue 549

Scramble for container and vessel capacity

One way carriers supported freight rates in the past was by “blanking” or canceling sailings to artificially limit transport supply (a practice carrier alliances are specifically allowed to coordinate under U.S. regulations). They did so in Q2 2020, when demand abruptly sank due to COVID lockdowns, and they’re likely to do so in the future when demand falls, extending the duration of rate strength.

But over the past year, as freight rates have skyrocketed, carriers have been doing the exact opposite: scrambling to inject whatever vessel and container capacity they can buy or rent into the market. The more ships and containers a carrier has controlled, the more money it has reaped from historically high rates. Virtually any container ship in the world that can float is now in service; the global inactive fleet fell to a fresh low of 2% in mid-January, said Alphaliner.

On the equipment front, containers are ordered at Chinese factories by liner companies or by companies that lease containers to liners. According to data from Drewry, last year’s new container production was by far the highest ever. A total of 7.18 million TEUs of new containers were produced, up 130% from the year before and 62% higher than the previous record set in 2018.

While it can take four months from order to delivery for new containers, it takes far longer — two or more years — from order to delivery for a new container ship. To compete for future market share, carriers went on an ordering spree. Alphaliner told American Shipper that tonnage on order is now 23.3% of on-the-water tonnage. At one point in 2020, it was down to the single digits.

To compete for near-term market share as they wait for their newbuilds, carriers have been leasing and buying ships at an unprecedented pace. Charter rates reached all-time highs last year — with some ships leased for as much as $200,000 per day — and average rates have further increased in early 2022. Meanwhile, a record 1.94 million TEUs traded hands last year in the secondhand sales market.

Another way to bolster near-term market share: Don’t scrap aging ships you otherwise would have. According to Alphaliner, container-ship demolitions collapsed to just 16,500 TEUs in 2021, “well below the 194,000 TEUs recycled in 2022 and a far cry from the 417,000 and 655,000 TEUs demolished in 2017 and 2016, respectively.”

MSC’s capacity had surged by 411,000 TEUs or 10.7% by the end of last year as the company bought over 100 vessels in the secondhand market. In early 2022, additional fleet gains pushed MSC past Maersk and MSC won the title of world’s largest ocean carrier.

Evergreen’s capacity jumped 15.6% last year. Zim’s (NYSE: ZIM) rose 14.9% as a result of charters. Capacity of Cosco, ONE and Pacific International Lines fell.

“Our year-on-year capacity comparison of the top 12 carriers shows major discrepancies between the winners and losers,” said Alphaliner.